The Onion Routing

Tor Network

Foundation

The concept of onion routing was initially developed at U.S. Naval Research Lab at 90’s to answer the challenge on how to communicate discreetly and without disclosing the participants over a network that is possibly monitored. At early 2000’s two MIT graduates started to further develop the concepts, which eventually paved way into forming a non-profit organization Tor Project Inc to maintain the development.

Onion Routing

Onion network is made of multiple relays, which serve three different functions in the routing:

- Entry / Guard: This is where the data is initially sent

- Middle: This is a hop in between the entry and the exit

- Exit: This is where the the data comes out of Tor back to open web

As none of the relays know both the origin and the final destination and external observer is only able to see something going in to an entry point or coming out from an exit point, this does a remarkably good job in obfuscating the actual participants in the communication. In addition, the relays are assigned randomly and the communication is rerouted every 10 minutes to make tracking even more challenging.

Transmitted data is initially secured using three layers of encryption, and one layer is peeled off on each of the relays. The final leg from exit node to the recipient is therefore unencrypted (of course you might want to encrypt a sensitive payload separately by yourself).

Image from tor-manual

Tor Browser

Tor Browser is a modified version of Mozilla Firefox, and while it’s possible to use Tor with other browsers, it’s generally advised against as they lack the security and privacy features implemented in the tor-specific version.

The official Tor Browser is available for multiple operating systems and also different languages, and the installation itself is as simple as installing any other software from internet. The ease of access and pretty much non-existent learning curve makes this an easy choice for anyone in need of secure communications or a way to circumvent monitoring and/or censorship such as the Great Firewall of China.

In addition to the general availability, easy setup and ease of use, the Tor itself is incredibly secure, and could be considered unbreakable, especially if you’re not backed by resources such as a large goverment intelligence agency.

Forensic analysis and Tor

So what are your options as an investigator, given that Tor is very easy to setup and virtually unbreakable?

Traces of Tor usage

As Tor effectively hides all the artifacts usually left from standard internet usage, the first step is to identify whether the target has used Tor to start with. Places to look into:

- Local filesystem for any tor related files or binaries. A hash-library generated from the publicly available tor distributions might be useful in identifying renamed files.

- Page- and cache files might have traces of tor usage

- Memory dump. While effective, this is a time critical activity as tor-browser does a good job of cleaning its traces from RAM after closing and even after minutes of idling.

The weakest link

As Tor itself is hard, it’s often more viable to attack the user instead. An obvious way is to target possible mistakes in browser settings or general behaviour, such as:

- Geolocation, user might have allowed websites to obtain his/hers location

- Allowed executables and browser extensions might open a possibility to execute e.g. a tracker extracting the real ip address on target users device

- Similar tracker code embedded in downloadables, such as videos

- Activities in open internet

- Usernames, accounts, email-addresses

- Timeseries correlation, such as user was identified using a tor browser while an illicit event took place in the dark web

Shavers & Bair 2016: Hiding Behind the Keyboard

Tor browser hands-on

Installation

Initial attempt was to load the bundled Tor-browser-package and get going

ubuntu@xubu-sandbox:~$ wget https://www.torproject.org/dist/torbrowser/11.0.10/tor-browser-linux64-11.0.10_en-US.tar.xz

ubuntu@xubu-sandbox:~$ tar -xJf tor-browser-linux64-11.0.10_en-US.tar.xz

ubuntu@xubu-sandbox:~$ cd tor-browser_en-US/

ubuntu@xubu-sandbox:~/tor-browser_en-US$ ./start-tor-browser.desktop

Launching './Browser/start-tor-browser --detach'...

./Browser/start-tor-browser: line 28: [: : integer expression expected

But it failed on missing CPU features with following message:

- Tor Browser requires a CPU with SSE2 support. Exiting.

The message presented obvious that the host (Apple laptop with a M1 chip) running the VM was not a good fit for this.

Internet and the lecturer however told that Tor should run also on arm-CPU just fine (albeit with some tinkering), so I decided to try an different approach.

Building Tor from source

As the Tor-browser bundle wasn’t available for the VM at hand, I took a workaround to build Tor standalone from the source code and setting it as SOCKS proxy to Firefox.

# Get a recent source, it's chekcsum and signature

ubuntu@xubu-sandbox:~$ wget https://dist.torproject.org/tor-0.4.6.10.tar.gz

ubuntu@xubu-sandbox:~$ wget https://dist.torproject.org/tor-0.4.6.10.tar.gz.sha256sum

ubuntu@xubu-sandbox:~$ wget https://dist.torproject.org/tor-0.4.6.10.tar.gz.sha256sum.asc

# Get signers PGP key

ubuntu@xubu-sandbox:~$ gpg --auto-key-locate nodefault,wkd --locate-keys dgoulet@torproject.org

gpg: key 42E86A2A11F48D36: public key "David Goulet <dgoulet@torproject.org>" imported

gpg: Total number processed: 1

gpg: imported: 1

pub rsa2048 2011-05-11 [SC] [expires: 2023-04-07]

B74417EDDF22AC9F9E90F49142E86A2A11F48D36

uid [ unknown] David Goulet <dgoulet@torproject.org>

sub rsa4096 2013-09-10 [E] [expires: 2023-04-07]

# Store key in keyring and verify the checksum against its signature

ubuntu@xubu-sandbox:~$ gpg --output ./tor.keyring --export B74417EDDF22AC9F9E90F49142E86A2A11F48D36

ubuntu@xubu-sandbox:~$ gpgv --keyring ./tor.keyring tor-0.4.6.10.tar.gz.sha256sum.asc tor-0.4.6.10.tar.gz.sha256sum

gpgv: Signature made Tue Feb 15 15:36:31 2022 EET

gpgv: using RSA key B74417EDDF22AC9F9E90F49142E86A2A11F48D36

gpgv: Good signature from "David Goulet <dgoulet@torproject.org>"

# And now that signatures check out, make sure that the source matches it's chekcsum

ubuntu@xubu-sandbox:~$ sha256sum -c tor-0.4.6.10.tar.gz.sha256sum

tor-0.4.6.10.tar.gz: OK

# Unzip, configure (or try to configure) and install the build

ubuntu@xubu-sandbox:~$ tar -xzf tor-0.4.6.10.tar.gz

ubuntu@xubu-sandbox:~$ cd tor-0.4.6.10

ubuntu@xubu-sandbox:~/tor-0.4.6.10$ ./configure && make && sudo make install

# Dependencies that were needed for the build to eventually succeed

ubuntu@xubu-sandbox:~/tor-0.4.6.10$ apt-get install libevent-dev

ubuntu@xubu-sandbox:~/tor-0.4.6.10$ apt-get install libssl-dev

ubuntu@xubu-sandbox:~/tor-0.4.6.10$ apt-get install zlib1g-dev

## Start tor

ubuntu@xubu-sandbox:~/tor-0.4.6.10$ tor

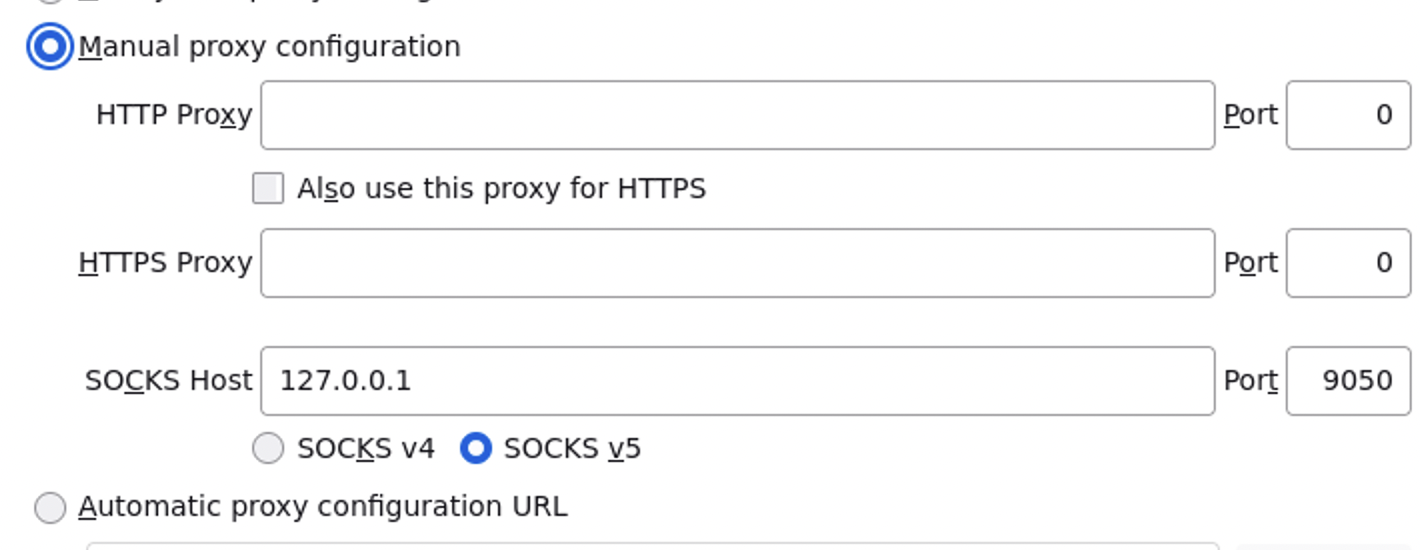

Tor proxy and Firefox settings

Tor was left with vanilla settings so the SOCKS proxy is served at its default location, port 9050 of localhost.

Firefox > Settings > General > Connection Settings

- Set “Manual proxy configuration”

- SOCKS Host: 127.0.0.1, Port: 9050

- SOCKS v5

- Select “Proxy DNS when using SOCKS v5”

Firefox Connection Settings

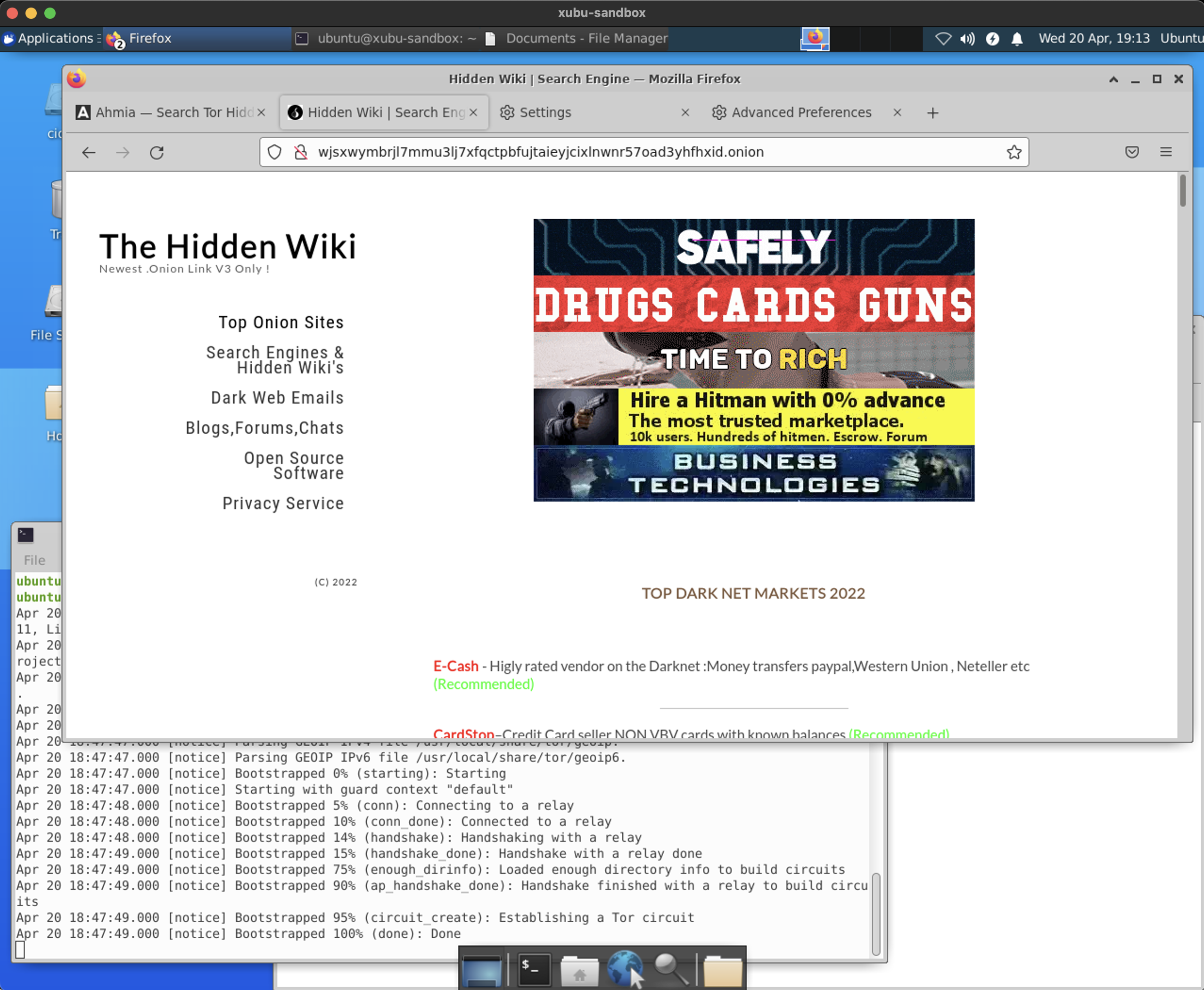

Enabling .onion services

Now checking e.g. https://www.whatismyip.com/ already shows that my ip-address and location are hidden from the service provider (in this case my location was initially shown as Warsow and some time later as Amsterdam).

Finally, in order to access the hidden .onion services, following setting needs to be set as false in Firefoxes about:config (in addition to enabling SOCKS proxy for DSN in the connection settings earlier):

- network.dns.blockDotOnion: false

It works! The dirty secrets hidden in onion-routed darkweb are now visible

- On a side note, the browser is still vanilla Firefox instead of the specialized fork included in the Tor-browser bundle, and as such it’s also lacking the security optimizations and other configurations done in favor of security and anonymity.

- I suppose greatest risks in using standard browser instead of the one supported by Tor Project:

- The browser might collect user telemetry and send it to a third party (i.e. Google Chrome)

- The possibility to mistakenly generate non-proxied internet traffic (e.g. DNS-requests exposing the sites you’re trying to access)

- Getting hacked through a vanilla-browser weakness when visiting a malicious onion-service

- History and various cached files stored in the local filesystem

- It’s also a good idea to disable all executables such as javascript and possible extensions

- It’s even better idea to use the actual Tor-browser - using standard Firefox should be taken simply as a technical execise to get familiar with the basic concepts.

Compromizing a Tor users anonymity

Multiple examples of de-anonymization exist, and especially the ones involving criminal charges have raised a fair amount of publicity, and also some academic research.

Notable example from Finland is the arrest of Lasse Kärkkäinen, the founder of major national Tor-based online-marketplace for illegal substances called Douppikauppa. During 2014 FBI managed to locate and bring down a major international marketplace Silk Road 2, and by investigating the seized servers the authorities also got hold of at least some of the messages sent between buyers and sellers. Within the buyers was also a account called redword, who seemed to be trafficing large amounts of drugs into Finland via Netherlands.

FBI shared their findings with Finnish authorities, who then contacted Dutch autorities. Eventually after comparing the dates and locations of the the trade transactions obtained from the seized Silk Road files to Finnish residents located at the area in Netherlands at the same time, they were able to identify the person of mr. Kärkkäinen being the one that matches.

As in many other examples, the tor-network itself retained the users anonymity and the identification was established by correlating a trail of documented real world events to corresponding anonymous transactions in the dark web.

Tor alternatives

In addition to Tor, there’s also other projects thriving for user anonymity and lack of censorship. Common features are stong encryption schemes and decentralized arcitechture with peer to peer networking.

Links and references

- Shavers & Bair 2016: Hiding Behind the Keyboard

- Tor Project

- Tor Browser User Manual

- Nurmi 2019: Understanding the Usage of Anonymous Onion Services: Empirical Experiments to Study Criminal Activities in the Tor Network.

Assignment h4: https://terokarvinen.com/2021/trust-to-blockchain-2022/